- Magento 2: Defaults, uiElement, Observables, and the Fundamental Problem of Userland Object Systems

- Magento 2: Javascript Primer for uiElement Internals

- Tracing Javascript’s Prototype Chain

- Magento 2: uiElement Standard Library Primer

- Magento 2: Using the uiClass Object Constructor

- Magento 2: uiClass Internals

While part of a series on Magento 2, today’s topic is another pure javascript adventure. We’re going to run through some debugging techniques for tracing the javascript object prototype chain, the one we mentioned in our first javascript primer. Even if you think you understand this, you may want to read all the way through.

This article finally puts some of my own confusions around prototypes and javascript object inheritance to rest after over a decade of using this stuff.

The Problem

Trying to trace a javascript object’s hierarchy, or trace backwards through its prototype chain, can be difficult. That’s because

- Until very recently, there was no way to reflect into an object’s prototype

- Some of Javascript’s internal objects/functions have a property named

prototypethat is not that object’s javascript-prototype object.

Right now, the de-facto in-browser way of checking an object’s parent object (i.e. its prototype object) is to use the __proto__ property.

var foo = {}

console.log(foo.__proto__);

This property started life as a proprietary browser vendor implementation, but based on this callout from the Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) it sounds like __proto__ was formally added to ES6, but immediately deprecated in favor of the new (and as yet unimplemented in browsers) getPrototypeOf.

Following the ECMAScript standard, the notation someObject.[[Prototype]] is used to designate the prototype of someObject. This is equivalent to the JavaScript property proto (now deprecated). It should not be confused with the func.prototype property of functions, which instead specifies the [[Prototype]] of all instances of the given function. Since ECMAScript 6, the [[Prototype]] is accessed using the accessors Object.getPrototypeOf() and Object.setPrototypeOf().

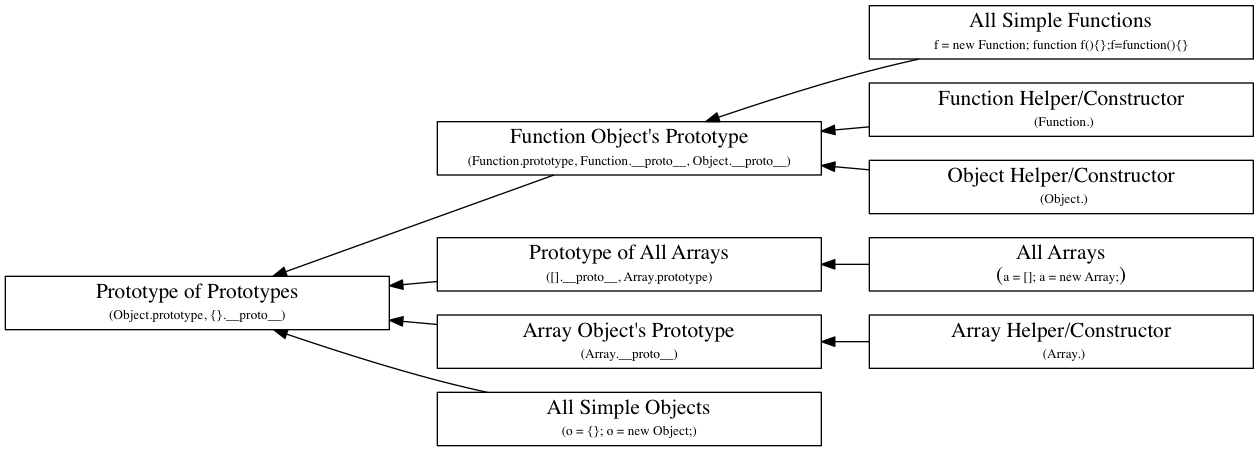

Where things get confusing is a few of javascript’s standard objects have a property named prototype that does not always point to that object’s prototype, but can create the impression it does. Those object are Object, Array, Function, and any instance of a function object.

The first three objects are sometimes called javascript’s global objects. Other times they’re called helper objects. Still other people call them javascript’s fundamental objects. Finally, they’re also referred to as javascript’s base type constructor objects.

Today we’re going to run through what the .prototype property of each one, and by the end we hope you’ll see why all the above descriptions are, in their own way, true.

The Object Helper Object

The first object we’ll talk about is the Object object. This is a globally available object that contains helper methods for programmatically interacting with javascript’s objects.

The Object object has a property named prototype. The property contains the object that’s at the top of javascript’s prototype chain. In other words, Object.prototype is the final parent object for all objects. It is also the object that javascript assigns as the prototype to objects created via an object literal.

foo = {};

console.log( foo.__proto__ === Object.prototype); //true

The tricky thing here? Object.prototype is not Object‘s prototype. Object is actually a grandchild of this top level object

foo = {};

console.log( Object.__proto__ === Object.prototype); //false

console.log( Object.__proto__.__proto__ === Object.prototype); //true

The Object.prototype property is a helper property that points to the object that’s at the top of the prototype chain. It’s in no way indicative of the Object object’s place in that chain. This has, for years, created some sort of cognitive dissonance in my head whenever I start dealing with these objects, and I think I finally understand why.

This “prototype of prototypes” is very important to javascript’s object system. It’s the bedrock that the entire object system relies on. When we’re doing systems level coding that requires us to look at this object, our instincts are

we should have access to it via a global object of some kind.

We don’t. The only way to access to parent-of-all-objects is via an object that is a grandchild of that object (i.e. Object).

The fact our access comes via a property of Object (vs. a method like getAlphaPrototypeObject()) also confuses things. That it’s a property creates a strong indication (to the uninitiated) that it somehow represents a direct parent/child relationship between Object and Object.prototype.

Whether this design is the right one for client programmers is a different debate for a different time. However, for a systems developer (one who is, say, creating, debugging, or explaining a custom object system like Magento 2’s) the official APIs here are a little weird. This is often the case with systems programing, which is why good documentation and clear intentions are so important.

The Array Helper Object

The next object on our list in the Array helper object. This object provides helper methods for creating and working with javascript arrays. This object also has a property named prototype. The property does not point to Array‘s javascript-prototype

console.log(Array.__proto__ === Array.prototype); //false

Instead, it points to the object prototype for all array objects.

foo = [];

console.log(foo.__proto__ === Array.prototype); //true

Similar confusion to Object.prototype can happen here as well. Array is simply a helper object that provides access to the prototype object for all arrays via a .prototype property.

The Function Helper Object

Next up is the Function helper object. I bet you’ve already guessed that this object is another helper object, one with methods for creating and dealing with javascript functions. This object also has a .prototype property. However, in a switch up, Function.prototype is the Function object’s prototype.

console.log( Function.prototype === Function.__proto__ ); //true

Also, unlike Object.prototype and Array.prototype, the Function.prototype property is read only. You can’t add properties to it or replace it like you can with Array.prototype and Object.prototype.

Individual Function Objects

The last .prototype property we want to look at is the .prototype property of individual function objects.

function foo(){};

bar = function(){};

baz = new Function;

console.log(foo.prototype, bar.prototype, baz.prototype);

The .prototype property is not the function’s prototype.

console.log(foo.prototype === foo.__proto__); //false

Instead, this .prototype property is a new object, created whenever your create a new function. At the time of creation, this .prototype object is not any object’s prototype. However, if you use this function as a constructor function (with new), the function’s .prototype property will be assigned as the new object’s prototype.

var Foo = function(){};

object = new Foo;

console.log(object.__proto__ === Foo.prototype); //true

This is another area where things can get super confusing. Consider the following statement — do you think this is true or false?

When you create a new object with the

new Foosyntax, javascript will assignFoo‘s prototype as the new object’s prototype.

That statement is true, in that javascript will assign the property named prototype as the new object’s javascript-prototype. However javascript will not assign Foo‘s javascript-prototype (available at .__proto__) as the new object’s prototype.

I’m sure, for some of you, this is a very “wonky” distinction to make — but if you have any hope of reasoning correctly about javascript code that uses these properties, it’s also a hugely important distinction to make.

Helper Objects as Constructors

If we consider the behavior of the .prototype property of simple function objects, the .prototype properties of Object, Array, and Function suddenly become clearer. These objects, in addition to containing helper methods, are also constructor functions

o = new Object;

console.log(o.__proto__ === Object.prototype); //true

a = new Array;

console.log(a.__proto__ === Array.prototype); //true

f = new Function;

console.log(f.__proto__ === Function.prototype); //true

Just as it would with a userland function, javascript will look to the prototype property of these objects when they’re used as constructor objects, and use that property as the new object’s javascript prototype.

Again, when talking about these objects in a system’s programming context, it’s important to make a distinction between an object’s javascript-prototype, and a function’s .prototype property.

This is an area where a lot of well meaning tutorials can cause some confusion. For example, it’s common for code like the following

o = {};

o = new Object;

to be described (ambiguously) like this

The

ovariable will become an object of typeObject

This isn’t exactly true. From a strict, prototype inheritance view of the universe, the o variable will have Object.prototype as its parent object. However, if you view the diagram below, you can see that instantiated objects (“All Simple Objects”) are actually higher in the hierarchy chain than Object objects.

This confusion, like a lot of javascript, can probably be traced back to its infamous 10 day creation myth, followed by years of careful, backwards compatible engineering.

The Constructor Property

This is also probably a good time to mention the .constructor property of instantiated objects. In a newly instantiated object, this property will point to the constructor function that created the object.

In other words

Foo = function(){};

object = new Foo();

console.log( object.constructor === Foo); //true

Wrap Up

Alright! With javascript’s entrails read, our next step is a to review a few important modules and methods in Magento’s standard RequireJS library. These modules are used heavily in the uiElement object system, and it’s important we cover them now before venturing further.